I had the honour of being selected to speak at Agile Scotland in March, 2020. The topic for my presentation was Creating The Right Conditions For Change, and I based this talk on my work on setting up Communities of Practice at work.

I’ve included the slides and some very brief speaker-notes below. Let me know if you’d like to know more, or if you’d like me to come talk at you event!

On mobile you can swipe left/right to advance the slides.

-

-

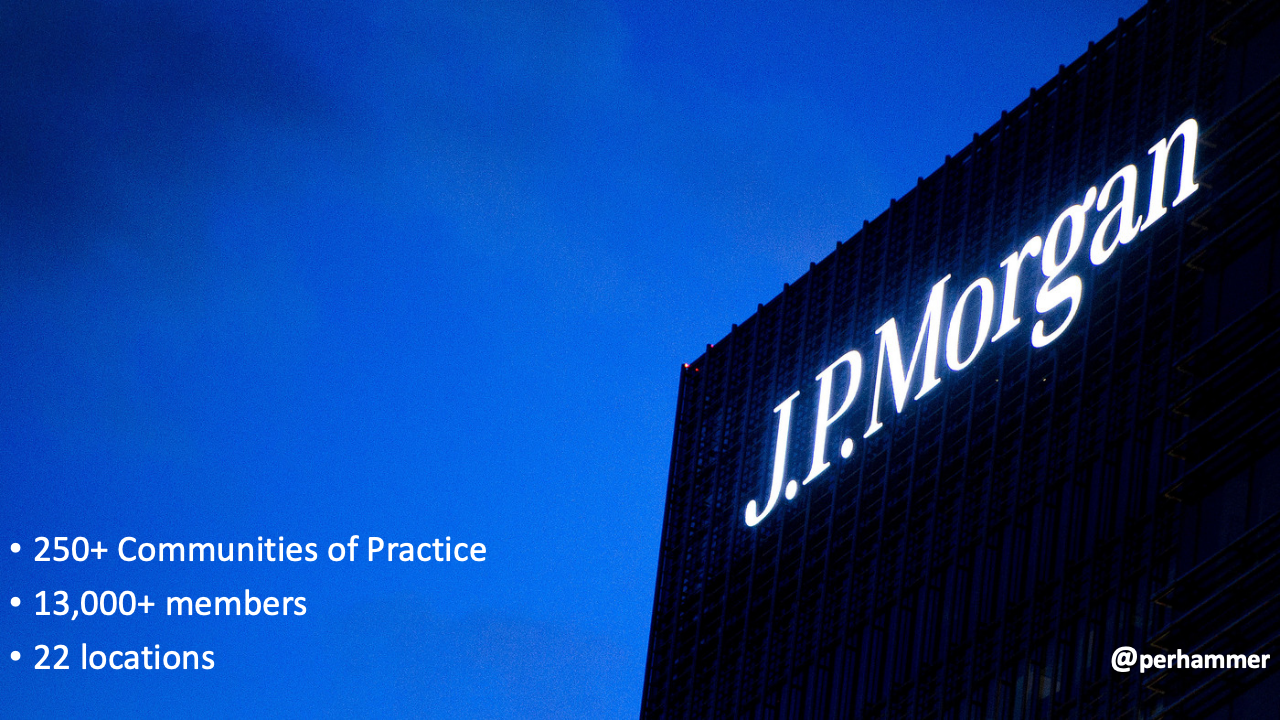

About Us

We're A Big Bank™, but we're also a very big technology employer. And we're always hiring. Come work for us, check out jpmorgan.com/techcareers -

What Doesn't Work

Before diving into how to create the right conditions for large scale organisational change, let's take a quick look at some of the challenges that make this difficult. -

Theory Of Planned Behaviour

Proposed by Icek Ajzen in 1985, TPB says that an individual's behavioural intentions are shaped by three core components: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. To effect change (in behaviour), TPB suggests changing one (or ideally all!) of the three core components. For example, by changing the "subjective norm" for some specific type of behaviour.

This often fails for a variety of reasons; it ignores the individual's needs, and the individual's emotions towards engaging in specific behaviours. -

-

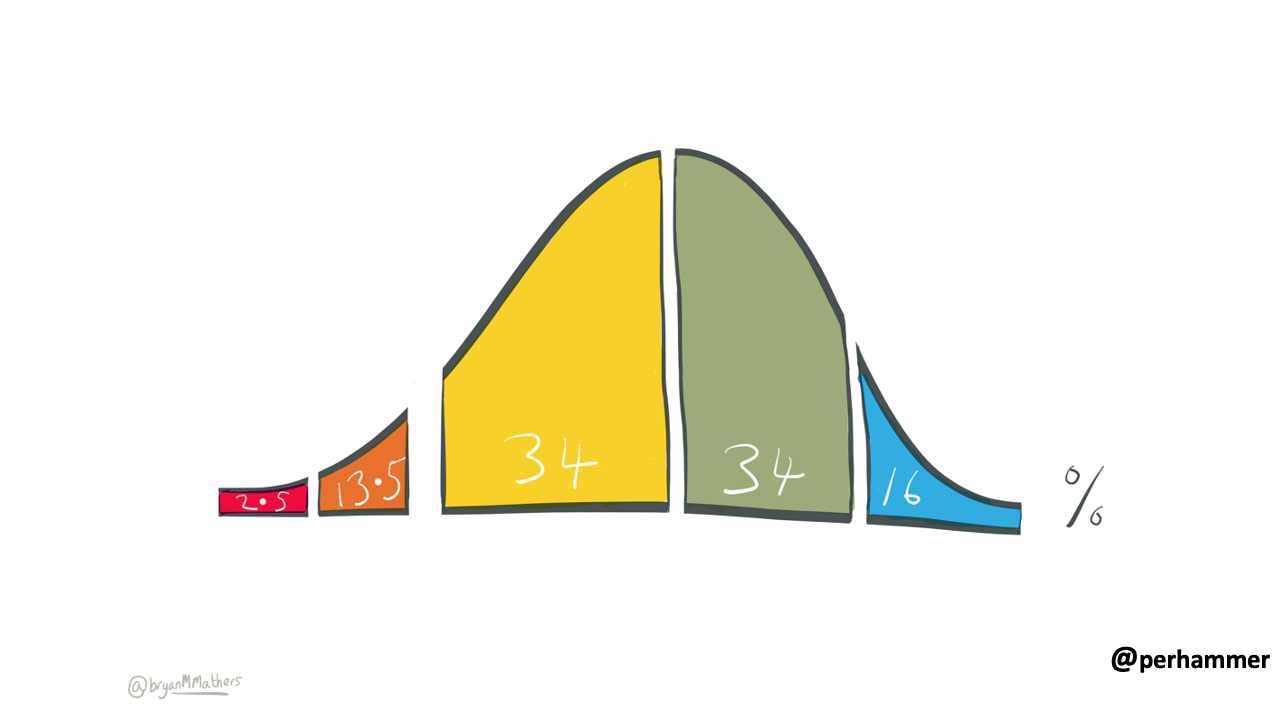

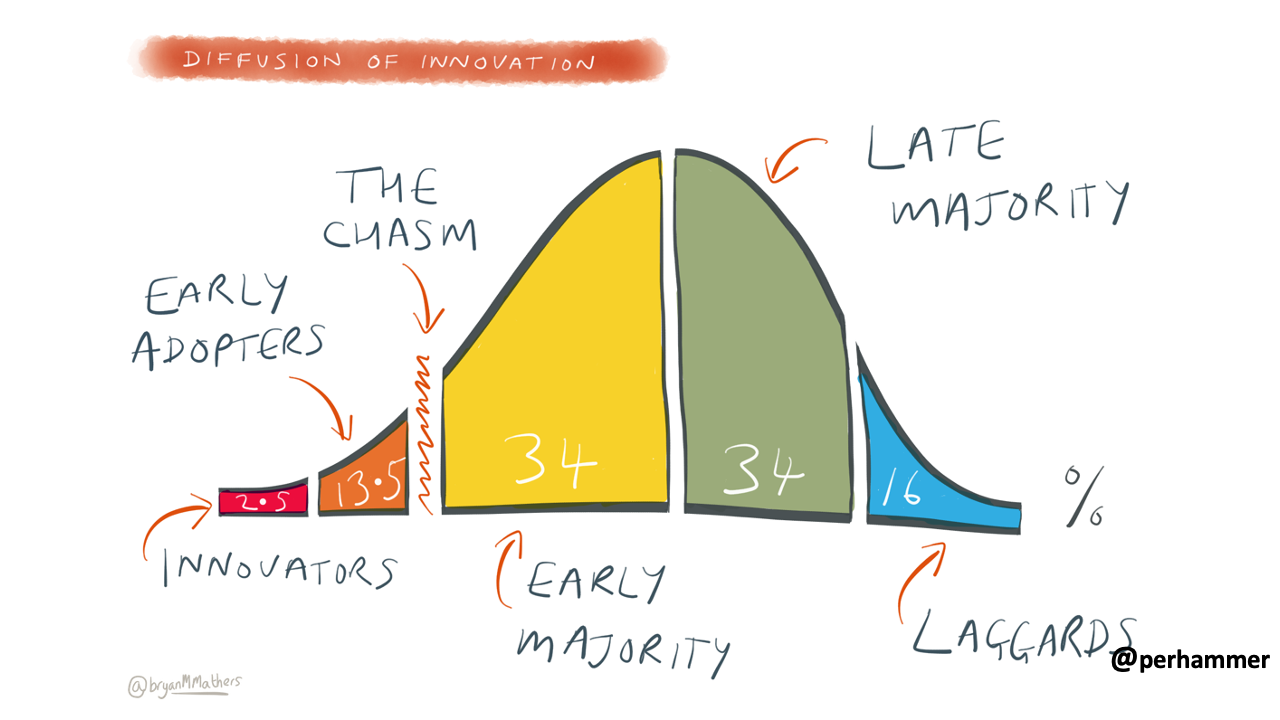

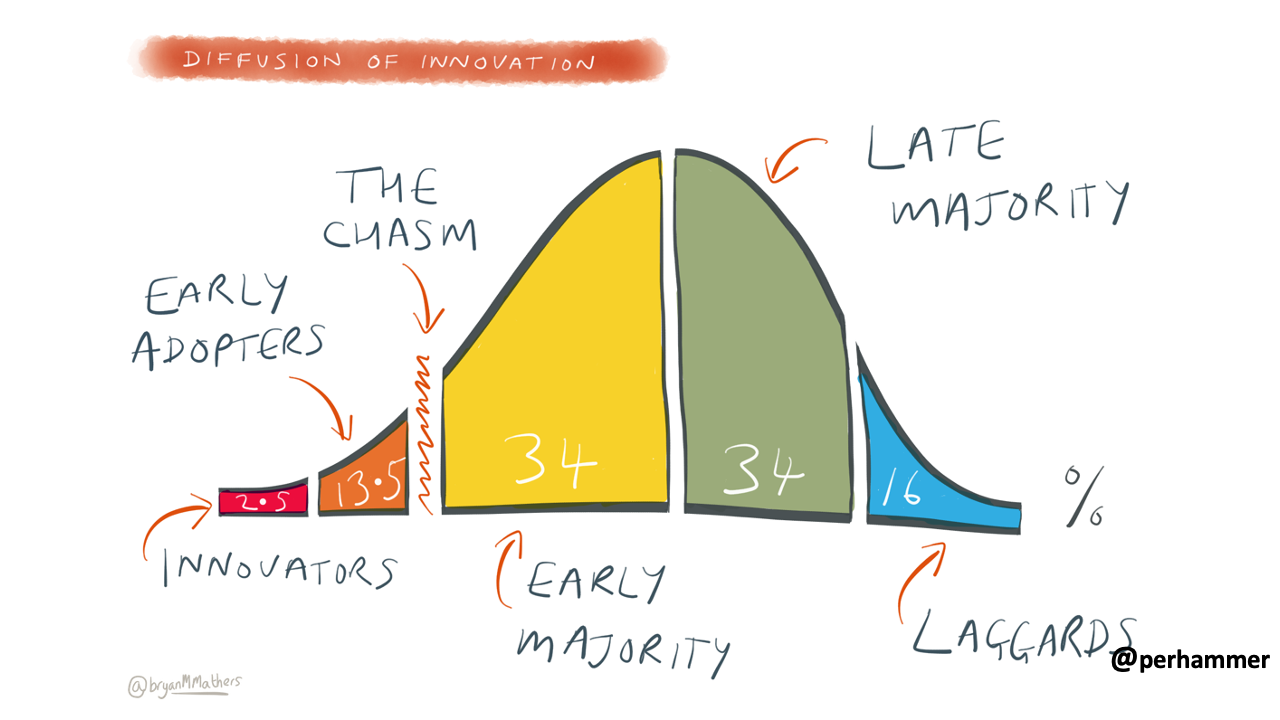

Diffusion Of Innovation

Many of you are probably familiar with this curve, so I won't say much about it here, but instead come back to it in more detail a little later.

(Apologies to @bryanMMathers for retouching his illustration, I'll use the unaltered version later.) -

-

Our Story

Our story begins in 2016, at Lean Agile Scotland, where Emily Webber did a great talk entitled "Communities of Practice, the Missing Piece of your Agile Organisation". One of my colleagues attended the talk, and came back to the office super inspired.

He grabbed me and a handful of other, likeminded people and asked - -

Cool If?

Wouldn't it be cool if we had some Communities of Practice? And they were easy to start, were long-lived, and had legitimacy? (Actually, we didn't think about legitimacy at the time - we learnt about that later, but I'll get back to that.)

We'd already had some Communities of Practice, but they tended to be short-lived (1-2 years) as they relied too heavily on too few key people to be sustainable over long periods, so we set out with a strong focus on sustainability. -

Community In A Box

We kicked the idea around for a while, it probably took six weeks, but in the end we came up with a brand and a concept that seemed to stick. We called it Ignite and the idea was to provide "a community in a box". On the slide here you see some of the boxes, and the first eight communities we launched receiving their boxes. (more) -

What's in the box? Our idea of "everything you need to run a community meet-up": a couple of coffee-mugs for the community co-leads, a bundle of lanyards for the community members, Sharpies and Post-its for the meet-ups, and a copy of Emily's book about Building Successful Communities of Practice. The box also contains a catering-voucher for the first community meeting.

What's in the box? Our idea of "everything you need to run a community meet-up": a couple of coffee-mugs for the community co-leads, a bundle of lanyards for the community members, Sharpies and Post-its for the meet-ups, and a copy of Emily's book about Building Successful Communities of Practice. The box also contains a catering-voucher for the first community meeting.

Also in the slide - our community launch-pad. Our communities are driven by interest rather than mandate, so we created a simple website for colleagues to propose and support new communities being created. We also have a small team of volunteers to regularly review the launchpad and provide launch-assistance for new communities. -

Four Years Later

That was 2016. It is now four years later, and we have over 250 Communities of Practice, with over 13,000 members, in 22 locations. -

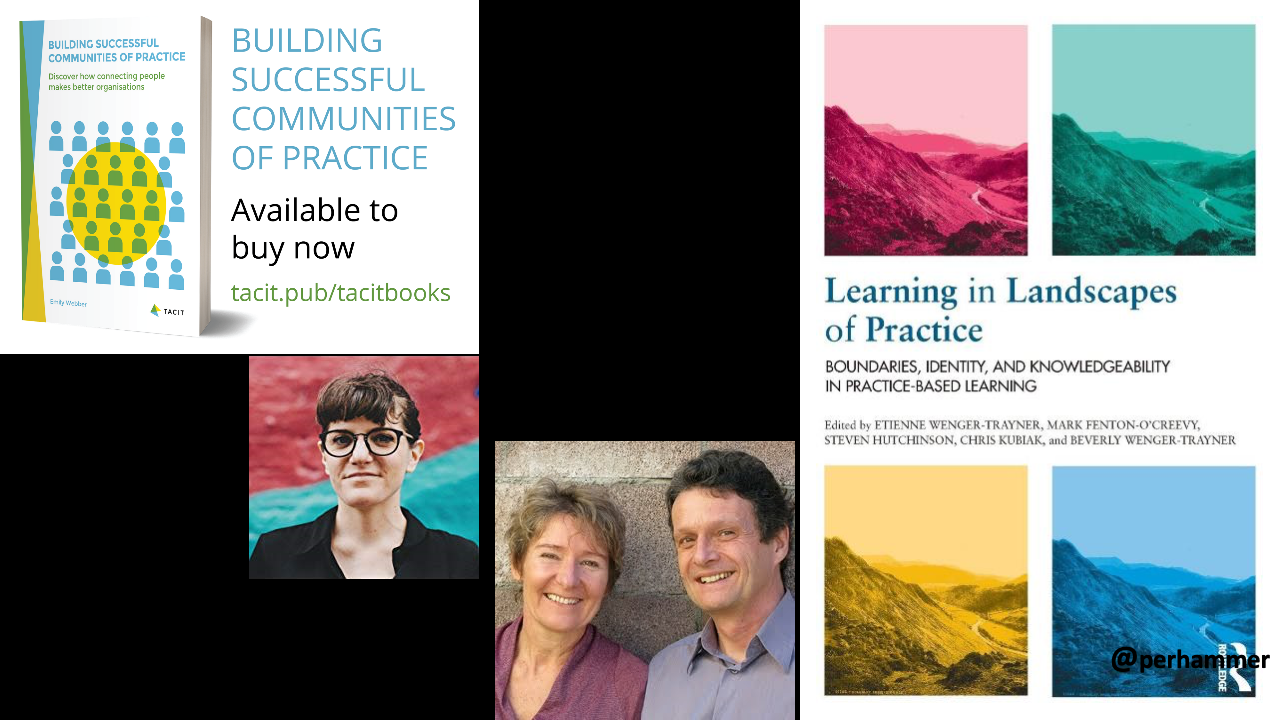

Learn More: Emily

To learn more about Communities of Practice, watch Emily's talk from 2016, or read her book. Both are great, and we wouldn't be here without them. -

Learn More: Bev and Etienne

Remember I said we didn't know about "legitimacy" of Communities of Practice when we first started? We learnt about that from Beverly and Etienne Wenger-Trayner. Their book Learning in Landscapes of Practice covers a lot more about the social-learning theory behind Communities of Practice, and helped us evolve our thinking and approach beyond starting the first few communities in Glasgow. And we're still working with Bev and Etienne to continue to grow our understanding of social learning in an "Enterprise" setting. -

Learn More: Come visit (or talk to) us!

And finally - if you'd like to know more about how we did it, we're always happy to talk! Just tweet me and I'll set it up. (Or email me, link at the bottom of the page!) -

Note the asterisk

Why did it work? We have some theories... -

Trojan Horse

Esther Derby has talked about how "Big changes feel like existential threats. Small changes support learning." When we first started this, it was a small change.

Peter Senge said "People don't resist change. They resist being changed." Because our Communities of Practice are interest-driven, people didn't feel like they were "being changed". (more) -

Also, because we started small, and stayed close to the organisation's goals, we didn't trigger a response from the corporate immune system. More about that in a minute.

Also, because we started small, and stayed close to the organisation's goals, we didn't trigger a response from the corporate immune system. More about that in a minute.

Finally - our Communities of Practice act like a double Trojan Horse: we got Communities of Practice into the organisation, and we got people engaged in Communities of Practice, without anyone noticing we were running a change-program. -

Corporate Immune System

No corporation reaches significant scale without also developing a considerable corporate immune system. This system is adept at detecting ands resisting change, both officially sanctioned change as well as corporate rebels. -

Diffusion of Innovation

Popularised by Professor Everett Rogers as early as in 1962, Diffusion of Innovations Theory looks at how new ideas spread. It suggests four elements that influence the spread: the innovation (or idea) itself, communication channels, time, and a social system.

The categories of adopters are innovators, early adopters, early- and late majority, and laggards. Geoffrey Moore wrote a book called "Crossing the Chasm" where he identifies the "chasm" as the gap between the Early Adopters and the Early Majority. For an innovation or idea to gain widespread use, it needs to cross this chasm. -

Recap: we have 51,000 technologists. And I just told you we have 13,000 members in our Communities of Practice, putting us at 25% adoption - not into the Late Majority yet, but over the chasm and starting to make in-roads into the Early Majority.

Recap: we have 51,000 technologists. And I just told you we have 13,000 members in our Communities of Practice, putting us at 25% adoption - not into the Late Majority yet, but over the chasm and starting to make in-roads into the Early Majority. -

Barriers to Change

Dunbar's Number: proposed in the 1990s by antropologist Robin Dunbar, Dunbar's number is a correlation between primate brain-size and average social group size. For humans, Dunbar suggests we can, on average, "comfortably maintain 150 stable relationships." Modern organisations, and modern offices, frequently bring far more than 150 people together in a close, social setting. This overwhelms our "social brain" and can result in uncooperative or even anti-social behaviour. (more) -

Gradual Erosion of Trust: "Enterprise" change-programs often arrive with significant fanfare, make a lot of noise and superficial change, but ultimately fail to leave lasting, deep changes in their wake. Over time, these programs erode trust and leave increased cynicism (and change-resistance) behind.

Gradual Erosion of Trust: "Enterprise" change-programs often arrive with significant fanfare, make a lot of noise and superficial change, but ultimately fail to leave lasting, deep changes in their wake. Over time, these programs erode trust and leave increased cynicism (and change-resistance) behind.

Lack of Opportunity: There are a lot of disenfranchised workers out there who feel they lack the opportunity to participate in the evolution of the workplace. -

Activation Thresholds: Ever tried pushing a car? Notice how hard it is to get going, and then relatively easier to keep going once you do? That's an "activation threshold", and organisational change is similar - it's easier to keep it going once you get it started.

Activation Thresholds: Ever tried pushing a car? Notice how hard it is to get going, and then relatively easier to keep going once you do? That's an "activation threshold", and organisational change is similar - it's easier to keep it going once you get it started. -

Conditions for Change

Build your change-programs to "start lots of little fires" (another Esther Derby phrase) and have them be mutually supportive of your overall change-program. Think "change networks" rather than "change agents".

Work top-down and bottom-up. Doing only one or the other doesn't work. -

Concentrate on serving the people who turn up. We call this "celebrating the choir".

Concentrate on serving the people who turn up. We call this "celebrating the choir".

It's ok to have different narratives for different audiences, this makes it easier to tap into their "enlightened self-interest" to encourage them to participate. -

You don't need a multi-step, multi-year plan to get started. Find a step that "isn't obviously backwards" and try it. Then iterate. This helps overcome the activation threshold and analysis paralysis. You probably DO want a strategy once you get going, though.

You don't need a multi-step, multi-year plan to get started. Find a step that "isn't obviously backwards" and try it. Then iterate. This helps overcome the activation threshold and analysis paralysis. You probably DO want a strategy once you get going, though.

Engagement, and participation in your change-programme, is a renewable resource, but you have to make sure you keep adding value for your participants. -